Over the last few weeks, we’ve been dealing with some heavy fallout from a recent server migration on our large WordPress MU installation. While moving everything from Linode to Digital Ocean should give us a more powerful toolset, save on costs, and give us more infrastructure flexibility, I wish the cut over was uneventful.

On Friday we spent the better part of our day working with the team at Reclaim Hosting to troubleshoot some issues we were having, and one day I or one of my other compatriots might feel brave enough to document that crusade in a post to enshrine the great display of teamwork that pulled off a clutch save. Or write the other post shaming us for our poor testing patterns : )

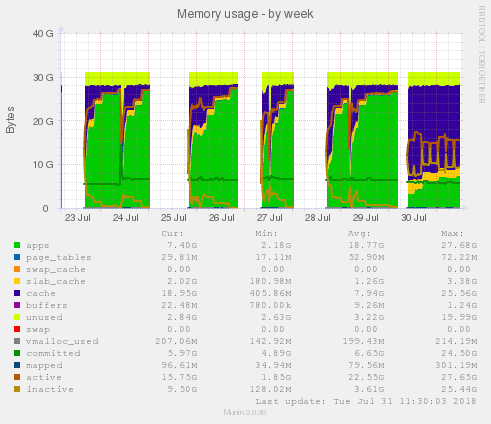

However, after the switch sat for a few days, we ran into a scenario where MySQL started to eat through the available memory on the server, all the way up to 96 GB of RAM. Obviously this was unsustainable, so Tim at Reclaim suggested swapping out MySQL for MariaDB, which is a drop-in enhancement for MySQL.

Tim wired this up on our staging server, and it seemed to pretty immediately level out our database performance. However, we wanted to do some basic load testing of this new setup to make sure that performance would stay the same as our usage increased.

You can see some of these represented in the dramatic drop in the green part of this area chart below:

After that new usage level stayed stable for a day or so, we decided to do some load testing on both servers to test some of these assumptions. Once we got down to it, we felt like existing load testing tools didn’t give us a great picture of how our setup might get hit under live load.

For example, we use NGINX as a proxy to Apache, and NGINX does a great job of caching frequently used resources. However, since we have 30K sites on this multisite, we’re not talking about tons of traffic to a few popular pages; instead, we are looking at fresh loads on lots of different sites, which might actually impact SQL performance.

When NGINX responds with a cached page or asset, nothing actually gets through to MySQL at all.

Since most existing load testing tools let you focus on throwing a lot of traffic at a few urls, we decided to write up a quick testing script that would loop through a larger CSV file of our 100 most popular sites as per our analytics data.

You can find a link to the GitHub repo here, but I posted the meat of the code below:

import csv

import requests

import chardet

import time

def check_traffic():

while True:

with open('./page_urls.csv', 'rb') as csv_file:

result = chardet.detect(csv_file.read())

with open('./page_urls.csv', 'r', encoding=result['encoding']) as encoded_file:

rows = csv.reader(encoded_file)

for row in rows:

url = "http://staging.rampages.us/" + row[0]

print("getting url: " + url)

r = requests.get(url)

res = {"url": url, "status_code": r.status_code, "test": r.text }

print(res)

time.sleep(.2)

check_traffic()

This quick script did a great job of getting a ton of requests past the NGINX caching on an initial pass, which let us evaluate the performance metrics we were interested in on the backend. However, this was a pretty manual process of logging into the server via SSH, running the top or htop command, kicking of the load test via local command line, then monitoring the top output in a separate terminal window.

While this was helpful for our particular purposes, it really highlighted to us how far some of the load testing tools need to grow in terms of their usefulness, especially for the non-standard WP set-up, once you get outside of caring about latency at a single url.

In our wrap-up discussion, we talked about where we think load testing for WordPress should head in the future:

- Easy plugin installation to allow load test to perform post creation, post update, comment creation, and media uploads as a part of the load test. For anyone using WP MU as an authoring platform, once you hit a certain scale, reads on your database aren’t the biggest deal, it’s when you have 1000 authors working at the same time that things start to move sideways.

- Anyone running a large WP installation knows that plugins and even perhaps themes are not made and distributed equally. Thus, focusing on one or two main URLs can lull us into a false level of confidence regarding how other sites, maybe less under our direct control, are performing.

- Actually simulate browser traffic instead of examining latency with just the initial HTML response. For example, the tool loader.io makes 10,000 or more requests to the same URL and tracks the response time for each request. However, this isn’t really helpful in getting the full picture of how your site would respond under actual load. When the browser parses your HTML, it fires off additional script/style/asset requests that will all place additional load on your server. It is easy to see from a data transfer perspective why the load testing companies don’t simulate a browser. In our test with 500 clients, our total bandwidth consumption for all of the tests was somewhere around 5 MB, but when I calculated the cost to have 500 clients download the entire page weight, it was somewhere around 2.5 GB.

- Right now, it seems like most performance testing tools involve chucking way more clients than realistic at a site so that we get a feel good sense that things are working well. But for most of us, 10,000 clients in 5 minutes downloading a single cached HTML page is far from realistic. We think it would be cool if a load testing tool could integrate with your Google Analytics data to simulate a load that would be realistically stressful for your application using historical data.

Overall, this has been an exciting foray into a part of development I’ve never really touched, but at the end of the day I’m left feeling disappointed by the existing options out there for load/performance/stress testing, especially when related to WordPress. I’m interested in how other people in the community handle this. I’m sure I’ve overlooked more capable tools, or sussed out problems that don’t exist for the community at-large.